Carved

by glaciers and blanketed with majestic hemlock, spruce, and cedar, the

coastal islands which form the Alexander Archipelago, many of which are

the size of small states, are part of the earth's largest temperate rain

forest. A host of unique wildlife inhabits the old-growth forests found

here, and the nutrient rich waters around the islands support a diverse

ecosystem of marine life. Some of the largest populations of humpback

whales found anywhere make this area a summer home while feeding and

raising young whales born in the waters around Hawaii during the winter.

This region has a mild, maritime climate, making it a prime habitat for

bald eagles, sea lions, and porpoise. Roughly half of

the state's bald eagle population lives here, and where orcas and humpback

whales come to feed in the summer.

Carved

by glaciers and blanketed with majestic hemlock, spruce, and cedar, the

coastal islands which form the Alexander Archipelago, many of which are

the size of small states, are part of the earth's largest temperate rain

forest. A host of unique wildlife inhabits the old-growth forests found

here, and the nutrient rich waters around the islands support a diverse

ecosystem of marine life. Some of the largest populations of humpback

whales found anywhere make this area a summer home while feeding and

raising young whales born in the waters around Hawaii during the winter.

This region has a mild, maritime climate, making it a prime habitat for

bald eagles, sea lions, and porpoise. Roughly half of

the state's bald eagle population lives here, and where orcas and humpback

whales come to feed in the summer.

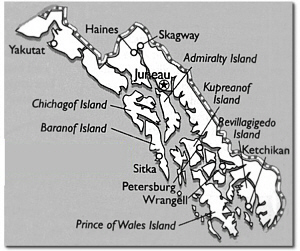

Some of these islands, such as Baranof, Chichagof, and Admiralty are

many miles in length and breadth. High mountains covered with dense

forests rise from the narrow beaches of the mainland and the larger

islands. Along the shores of the numerous inlets and channels are

scattered mining and logging camps, salmon canneries, and lonely little

towns. There are over 33 communities scattered mostly on islands through

Southeast. Juneau is the largest with about 30,000 people. Smaller

fishing villages may have only a few hundred residents. In the entire

region, roughly 70,000 people call Southeast home.

A compressed geography means that ocean tidewater brushes against 4,000

foot mountains capped by glaciers and ice fields. About 20,000 years ago,

during the Great Ice Age, virtually all of Southeast Alaska was covered by

ice. Only peaks reaching above 5,000 feet reached through the glaciers.

Today their sharp points contrast with rounded mountains that were

smoothed by the glacial advance. The ice retreated about 10,000 years

ago. Then about 2,000 to 3,000 years ago there was another, though

smaller, glacial advance called the Little Ice Age. Today's Southeast

Alaska glaciers are remnants of this last advance. They're the ones that

carved and polished the Southeast landscape we see today.

There are three major ice fields: the 1,500 square mile Juneau Ice

Field just behind the capital city, the slightly smaller Stikine Ice Field

near the communities of Wrangell and Petersburg, and the Brady Ice Field

in Glacier Bay National Park. Another dominating part of the Southeast

geography left behind by the glacier's retreat are the saltwater fjords.

Some still have active glaciers calving mammoth ice blocks into the ocean.

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, once called Thunder Bay because

of the roaring sounds made by falling ice, is the result of glacial

retreat. Situated about 90 miles northwest of Juneau, this grand

collection of tidewater glaciers is a wondrous blue ice land that

encompasses 3.3 million acres. The waterways provide access to some 16 of

these glaciers, a dozen of which actively calve icebergs into the bay.

This is a land comprising three climatic zones and seven different

ecosystems supporting an amazing variety of animal life: humpback whales,

Arctic peregrine falcons, common harbor seals, black and brown bears,

marmots, eagles and mountain goats, among many others.

|

Click on the picture for a larger view.

|

Man's habitation of the Glacier Bay region dates back approximately

10,000 years, but it appears that early settlers didn't stay here for very

long. As you can imagine, making a home around Glacier Bay was not easy.

Tlingit folklore includes tales of periodic village destruction from shock

waves and other natural forces. European exploration of Glacier Bay began

in 1741, when Russian ships of the Bering Expedition sailed the region's

outer coast. Glacier Bay was barely a dent in an icy shoreline when the

English explorer George Vancouver passed by nearly 200 years ago. At that

time, what is now the bay was filled with a wall of ice extending more

than 100 miles to the St. Elias Mountain Range. The face of the glacier

spanned over 20 miles, and in places it was more than 4,000 feet deep.

But, it wasn't until famed naturalist John Muir came to this icy

wilderness in 1879 to explore its flora and fauna that scientific

investigation and early tourism were spurred. On September 10, 1899, a

violent earthquake struck the Glacier Bay area. This caused enormous slabs

of ice from the Muir Glacier to calve, thereby choking the waterway.

Excursions to this sector ceased until 1925, when Glacier Bay National

Monument was established.

Hubbard Glacier flows over 90 miles through the Wrangell-St. Elias

National Park and Preserve to Disenchantment Bay, the head of Yakutat Bay.

While at present the Columbia is retreating, the Hubbard is advancing, as

it has for more than 100 years. In 1986, the Hubbard began a surge, a

period of rapid glacial advancement, which reached a dramatic climax

before the end of the year. By springtime, the glacier had completely

blocked off Russell Fjord from the sea, creating a rapidly rising

freshwater lake. On October 8, 1986 the dam gave way. A flood of ice,

water and debris crashed into Disenchantment Bay in a thunderous spectacle

that lasted for hours.

The Tongass National Forest, a 16.8 million acre rainforest managed by

the U.S. Forest Service, occupies 77% the Southeast Alaska land. Tongass

contains the largest tracts of virgin old-growth trees left in America and

is the world's largest temperate rain forest.

Towering mountains, cascading waterfalls, lush green forests and

magnificent glaciers make Misty Fjords National Monument one of America's

scenic wonders. Located in southeastern Alaska's wilderness area, the

over-2.2-million-acre region is also known for its wildlife, white sandy

beaches and unique ecosystems. Misty Fjords National Monument is a part

of the Tongass National Forest. The first of Alaska's 18 national

monuments, its rugged terrain supports many nearly untouched coastal

ecosystems. Alder and dense underbrush grow in places as high as the

timberline - about 2,000 feet above sea level - and lovely alpine meadows

are nestled in mountain valleys. Active glaciers on the northern and

eastern boundaries of the area date back to an ice age of thousands of

years ago. As recently as 1920, volcanic lava flows occurred near the

northern boundaries. Mineral springs are another distinctive geological

feature of the region, and veins of gold, silver, copper and other

minerals may be found in mountains that rise as high as Mount John Jay, at

7,499 feet.

The quiet and majestic beauty of Misty Fjords might be attributed to

the absence of human activity. Traces of the first human inhabitants

reveal that as early as 10,000 years ago Tlingit and Haida societies

settled here, and evidence of early American occupation may be found in a

few places. However, today the area is uninhabited and retains its

primitive beauty.

Tracy Arm, south of Juneau in Alaska's Panhandle, finds sheer cliffs

rising 3,500 feet from the sea, imposing tidewater glaciers. During the

late 1800s, explorers to this area survived courageous trips through the

rapid waters in small boats and canoes. In 1889, a survey team led by

Lieutenant Commander H. B. Mansfield named the now-preserved wilderness

Ford's Terror. Once the explorers made the trip up the rapids, they

saw a world that had undergone few changes since the last ice age. Tracy

Arm - Ford's Terror - is one of several remote locales preserved as a

national park, monument and wilderness area. Twin Sawyer Glacier calves -

massive chunks of ice break and plunge into the ocean. On South Sawyer

Glacier, seals often cavort on the ice in front of the glaciers. The ice

serves to protect young pups from killer whales, and the sector provides

an excellent food supply for the animals. Within its 656,000 acres of

undeveloped terrain, varied sea and bird life as well as brown and black

bears, goats and eagles call Ford's Terror their home.

Southeast Alaska has a unique heritage of seafaring

people that stretches back in time over 10,000 years to the camps

of the first people of the Northwest Coast Tribes. Alaska Natives continue

their ‘partnership with nature’ through preservation of their unique

traditional lifestyle. A rich oral history, passed from generation to

generation, tells of a presence on the continent from ‘time immemorial’.

The rain forested islands of the Inside Passage contain thousands of sites

and locations portraying a variety of ancient activities of a culture that

has long relied on a seafaring lifestyle in addition to the handful of

present day shore side Native villages.

Most of the communities are coastal and have limited or no road access.

The mountains and islands make road-building between many communities

impossible. Haines and Skagway are the only communities in Southeast

Alaska that are accessible by road. For this reason travel by plane and

boat is popular. Like the coastal Indians that paddled cedar canoes along

Inside Passage waterways, modern travelers use Alaska state ferries to

connect port with port. Large and small cruise ships, charter boats, and

private yachts call at picturesque towns and scenic wonderlands like Misty

Fjords National Monument, Tracy Arm, and Glacier Bay National Park and

Preserve, located near the capital city of Juneau. Highway access from the

contiguous states comes at Haines, Skagway, and the friendly ghost town of

Hyder, on the British Columbia border. Scheduled airlines and charter air

taxis and boats are the workhorses of southeast transportation, providing

dependable access to remote and nearby locations. Because the Southeast

is full of islands and mountains, transportation to remote areas is by

float plane or boat.

Southeast is Alaska’s “banana belt” - a land of giant trees and

rainforests where wet and mild are the best terms to describe the

Southeast's climate. High 40'sF to mid 60'sF are the summer norms, under

cloudy skies. On rare sunny days in summer, high temperatures might reach

the mid-70 degree range. Winter temperatures rarely fall much below

freezing. The record low in Juneau is minus 22, compared

to minus 34 for Anchorage and minus 61 for Fairbanks. The

panhandle receives from 30 to 200 inches of snow in the lowlands and more

than 400 inches in the high mountains. Considered an

annual average is 160 inches of "liquid sunshine" (rain).

The region's economy revolves around fishing and fish processing,

timber, and tourism. Most of the people that live in the southeast earn a

living by either logging or fishing. Spruce, hemlock and cedar are

harvested by the region's timber industry, and cover many of the mountain

sides. Salmon, halibut, herring, shrimp, and crab are caught by

commercial, subsistence and sport fishermen.

Communities in the Southeast (Inside Passage) region are:

Angoon

Coffman Cove

Craig

Gustavus

Haines

Hollis

Hoonah |

Hydaburg

Hyder

Juneau

Kake

Kasa'An

Ketchikan

Klawock |

Kupreanof

Metlakatla

Naukati Bay

Pelican

Petersburg

Point Baker

Port Alexander

Port Protection |

Saxman

Sitka

Skagway

Tenakee Spring

Thorne Bay

Whale Pass

Wrangell

Yakutat |